What translating ‘Kusumabale’ meant to Susan Daniel, winner of the Sahitya Akademi award

[Susan Daniel– A translator’s note, in Scroll.in on Mar 07, 2020.ದೇವನೂರ ಮಹಾದೇವ ಅವರ ಕುಸುಮಬಾಲೆಯನ್ನು ಇಂಗ್ಲಿಷ್ ಗೆ ಅನುವಾದಿಸಿದ ಸೂಸನ್ ಡೇನಿಯೆಲ್ ಅವರ ಅನುಭವ ಬರಹ 7.3.2020ರ Scroll.in ನಲ್ಲಿ]

Daniel won the 2019 award for translating Devanoora Mahadeva’s ‘Kusumabale’, considered a particularly difficult text, from Kannada into English.

A translator’s note, if anything, can at best be a series of notes – some trilling highs from getting close to the mysterious creative impulse and some despondent lows that sees art as a ruse. As if to balance the two, is the delight of bringing to the English language reader some things s/he might otherwise never have read!

It all began with a meeting of friends at a literary conference in Mysore a few years ago. “Don’t venture,” I was warned. All the same I called up the author to be told that “a translation was in progress”. A couple of months later, as if to reward my enthusiasm I was asked to translate Chapter 11, for Steel Nibs Are Sprouting.

Returning to this fascinating novel after so many years, this time as the other reader (translator), I was convinced that the text demanded something else of me. To enter the seamless flow of the chant-like rhythms where language and emotion take the lead in turns, I had to bring to it a keener ear – a different kind of auscultation perhaps?

As a first step, I began reading the text aloud, listening in for what I could hear, for what I could overhear, till I thought I had heard the lines out.

My initial resolve to make it over into simple English without elevating the register so as to retain the simplicity of the original seemed a good way to begin. But when my screen showed me lines quite different from what resonated in my ears, I threw up my hands in despair.

Part of the problem (I was to realise later) was that Chapter 11 that I attempted first was translated from L Basavaraju’s verse format (not a word altered; only a different line spacing). While this made comprehension easier, being a very complex text even in the original, it introduced an element of dramatic play.

I first read Kusumabale soon after it was published and recall the responses it evoked, with readers and critics puzzling over how to read the novel; whether it was to be read as a folk epic, a poem, or a novel.

For a translator – the bar set high!

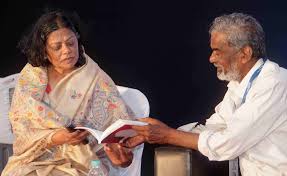

Having no first-hand knowledge of the Nanjangud dialect, I requested the author to help me out with a reading session. What awaited me in Mysore was a feast.

H Janardhan, who had set the Kannada landscape aflame with his soulful renderings of Dalit verses, was there. So too was Pramila Bengre, who played the part of Turamma in Basavalingiah’s stage version of the novel. Also, Shivaswamy, who had flawlessly committed the whole of Kusumabale to memory, kept watch to see I did not miss out on anything! Gratifying to say the least, and lofty terms like “intertextuality” and “polysystems” made more perceptible and tangible.

My first decision to stay with fidelity (in deference to the closeness with which language follows content in the original) found me in the somewhat strange role of filling kernels (from the Kannada) into shells (English). Given the syntax of the two languages, English being right branching and Kannada (Dravidian) left branching, the whole exercise itself was something like a game of chess against a mirror! More often than not, my lines looked skewed.

Then on to – if the syntax in the original isn’t skewed, why should the translation be?…and so on, looking for analogous ways, and deciding to pitch in with tone as a way out of the dilemma. There being no pan-Indian dialect of Indian English to speak of, nor a local Kannada variant to lean on, the decision was to stay with tone and travel with the cadences, relying on pace as pointer, the strategy, if one can call it one.

Of those pernicious punctuation marks, the less said the better. Following the need to replicate the effect created by the long vowel sounds, aided by the unending whorls of association in the progressive tense in the original, there was a need to be as sparing as possible with punctuation marks. But given to ambiguities as English is, this translation too was soon “colon”ised, commas and full stops taking over!

Cultural pointers and variants in language are not the easiest to accommodate. A conscious decision not to be overly descriptive, relying on an excessive use of words in parenthesis – this in deference to the extreme economy of language in the original; nor to be overly prescriptive, dropping footnotes on every page, in compliance with the momentum this translation was striving to build; in the end, the challenge before this translation – how to pare down language?

The frugal elegance of language in the original Kannada is partly achieved by the fascinating use of long vowel sounds which invoke a broody meditative mood that draws on myth, history, the fabulous, and the real in turns.

Replacing this with demonstrative pronouns and short vowel sounds and turning them over into the clipped accents of English – clearly not the best of choices, and one of the losses in this translation. On the other hand, giving credence to an inside rhythm – a way to cut back the loss, and give this translation a voice.

It can be said that Devanoora Mahadeva rides the overarching connotation of speech as “utterance” in the tradition of saint and mystic poets. The language of Kusumabale, consciously drawing on this intent of language that incidentally underlines the socio-ethical attributes of most languages in India. Strengthened by folk aesthetic traditions, the novel flouts stereotypes vis-à-vis the untouchables and lets us into the thinking, feeling, autonomous world.

Keeping an eye open for the many strands and working at making them available was both enjoyable and energising. Looking at ways to foreground these strands, at times this translation has had to embellish hidden connectives, at other times indulge in alliteration, bolding, or emphasising parody and irony in order to familiarise readers with the unfamiliar— irony sometimes easier to peddle than humour and the parody of caste equations and cultural attitudes to caste.

It is of interest that the more obvious aspects of caste lie in the prose passages – Channa and his Brahmin teacher, Amasa and the passion he stokes in the upper-caste Bhagavathy, or even the DDS march. Whereas the subtler dimensions are in the poetic passages and reveal threads that make up the hidden narratives of discrimination and exploitation.

All said, a translation into English is never without its snares. The call given by Baba Saheb Ambedkar to the Dalits, to embrace English in order to step over hurdles set up by casteism, is a justification of sorts. Still, a translation into a global language is always an act of aggression, with issues like “culturally disadvantaged” sometimes taking on a different slant in the makeover into English. Enhanced by the fact that there are as many kinds of English, as there are states (in India), and countries.

In some ways Kusumabale reenacts aspects of the whole self returning to consciousness. Subconscious contents, dreamtime visions, the emotional body, aspects of our lives that have been marginalised in society’s march ahead; sometimes neglected, at other times sacrificed, blotted out, or simply ignored. Every once in a while, one comes across a writer like Devanoora Mahadeva who helps us access all this lost and buried wealth of experience.

[Excerpted with permission from the “Translator’s Introduction” to Kusumabale, Devanoora Mahadeva, translated from the Kannada by Susan Daniel, Oxford University Press.]