How Do We Talk About the State of India Today?

(A write up in Art Review Asia on 24 March 2023, that addresses both Devanura Mahadeva’s RSS: Aala mattu Agala and the BBC documentaries- By Deepa Bhasthi. 24 ಮಾರ್ಚ್ 2023 ರಂದು ಆರ್ಟ್ ರಿವ್ಯೂ ಏಷ್ಯಾದಲ್ಲಿ ದೀಪಾ ಭಸ್ತಿ ಅವರು ಬರೆದ ಒಂದು ಬರಹ. ಇದು ದೇವನೂರ ಮಹಾದೇವ ಅವರ ಆರ್ಎಸ್ಎಸ್: ಆಳ ಮತ್ತು ಅಗಲ ಕೃತಿಯನ್ನು ಹಾಗೂ ಬಿಬಿಸಿ ಸಾಕ್ಷ್ಯಚಿತ್ರಗಳನ್ನು ಉದ್ದೇಶಿಸಿ ಬರೆಯಲಾಗಿದೆ. )

“Examining two recent cultural productions that raise alarm bells about how the country is being reshaped”.

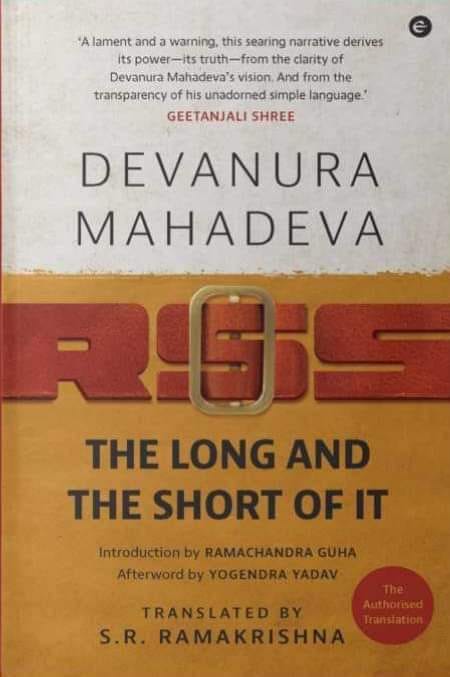

‘How many things do we talk about?’ wonders the award-winning writer Devanura Mahadeva in his latest book, RSS: The Long and the Short of It (2022), an analysis of the true nature and objectives of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ultra-nationalist, volunteer-led organisation from which India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) derives its political ideology. It is a useful question; the descent into violence, hate crime and religious intolerance in the nine years since Narendra Modi became prime minister has been so horrific that trying to prioritise what to talk about regarding India’s current sociopolitical scene is an unpleasant exercise in cleaving out all but the worst cases.

Mahadeva’s pamphlet-length book, written originally in Kannada – he is among the most influential writers in the language, which is spoken largely in Karnataka – and translated into English by S. R. Ramakrishna, approaches the topic head-on, redeploying the RSS’s own foundational texts in order to suggest that the organisation’s brand of ultranationalism is, in reality, anti-national and against India’s constitution.

In parallel, the recent BBC2 documentary series India: The Modi Question (2023) focuses, though not always very thoroughly, on some of the most controversial and disturbing of the government’s actions over the last decade and before it came to national power. While its two episodes tackle a vast number of topics, from pogroms and riots in Gujarat and Delhi to controversial citizenship bills and lynch mobs, the series remains cautious, trying too hard at times to include both sides of the story, but doing justice to neither.

Both the documentary and the book offer an entry point to understanding just how India has begun to redefine itself. In the former, the viewer is taken through ghastly videos of state murders and senseless mob violence, the police watch from a distance and do nothing to stop the violence, and the term ‘banana republic’ comes frequently to mind. It starts with the Godhra riots in Gujarat in 2002, a result of the burning of a train compartment with dozens of Hindu pilgrims inside, which led to the murder of hundreds if not thousands of Muslims in retaliation, reviving the allegation that the violence was engineered with the knowledge of Modi, then Gujarat’s chief minister (the Supreme Court exonerated Modi in 2022). The series claims that the British government has evidence from its own independent investigation that orders to ‘let it happen’ came from the top. It was this part that the Indian government has most objected to, banning all screenings, using intimidation and violence, and when it failed to keep the video files off the internet, raiding the BBC’s India offices in New Delhi and Mumbai on arbitrary grounds, a commonly used pressure tactic to discourage dissent.

The narrative of Hindu victimhood that solidified after the Gujarat riots helped Modi win the next elections, propelling him onto the national stage. He would continue using this myth of Hindus being in danger; from this first electioneering experiment in his home state, the politics of hate, buffered by vague ideas of fighting corruption and ‘good days’ to come, soon spread to the rest of the country. The documentary notes that Modi has never spoken up against hate crimes against Muslims and other minorities.

While the documentary is replete with deeply disturbing visuals, it is perhaps Mahadeva’s booklet that is the more frightening of the two; for in it, in characteristically minimal prose, he elucidates how the Modi government’s warpath to erase pluralism and tolerance in India can be traced back to RSS’s founding principles, inspired heavily by fascism in Hitler’s and Mussolini’s Europe.

The RSS – Modi and several members of his cabinet have been longtime members – was founded in 1925, and relies almost entirely on the four varnas, India’s infamous caste system, to define its vision for a Hindu state. According to the organisation, and Mahadeva quotes its early leaders K. B. Hedgewar, M. S. Golwalkar and V. D. Savarkar here, Hindus are ‘living’ gods; the Manusmriti (a text written in Sanskrit by Manu – current theories suggest it dates from somewhere between the second century BCE and the third century CE – that codifies Hindu customs and practice) should replace the constitution; race purity is an ideal to be achieved; and Sanskrit must be the lingua franca, with Hindi to be used ‘on the score of convenience’ until that is fully achieved. The RSS’s ideology is vehemently against the federal nature of India, calling instead for ‘one country, one state, one legislature, one executive, one flag, one leader’, an idea that no longer seems too farfetched when one examines the BJP’s more recent policy decisions.

The Long and the Short of It distils a big chunk of India’s economic, social, cultural and political problems into a calmly narrated tale of the country, helpfully including folklore to drive home Mahadeva’s call to action. The effect is as mesmerising as it is humorous. Likening the RSS to an evil magician, a master of disguise, an expert in hypnotism, whose life breath is hidden in a parrot that lives in a faraway cave, he says that the party’s power lies mainly in its faith in the caste system. Which is why, he explains, it will do everything possible to maintain the status quo in Indian society, divided and cut up in a thousand ways according to caste, sect and religion.

Along the way, he stops to comment on the spread of fake news, calling it ‘weed-like lies’ and noting that ‘fanaticism anywhere devours humanism’. He calls Modi an utsava murti, ‘a replica of the temple deity [that is] taken out [of the temple] during a procession’, whose only qualifications are the ability to put on a good show, to assist in emotional manipulation and to be able to create a scene to divert people’s attention from a bigger problem. Mahadeva also warns that the puppet show is designed by the deity inside the temple, not the one on the road, and the privileges of the utsava murti can be snatched away the moment the former decides it no longer has any use for the show idol. He thus suggests that real power in India is not with Modi or Amit Shah, his next-in-command, who are replaceable, but with the RSS, in its headquarters at Nagpur.

Another folktale: Mahadeva reminds us of the story of the evil Koogu Maari, where if one answers when she calls out one’s name, one vomits blood and dies a painful death. Safety rests in staying silent and writing ‘Naale Baa’ (come tomorrow) on the house door; so long as tomorrow never arrives, she is kept at bay. Urging his readers to exercise caution, Mahadeva writes that in the first instance they should ignore the calls of the Koogu Maaris of the RSS to join them in their ‘war of hate’. ‘The wisdom born from the experience of the countryside – that “divisiveness is the devil, oneness is god” – must become our wisdom too,’ he writes.

By the end of both the book and the BBC documentary, it is hard to hold on to a hope for immediate change; not when one is living through a progressively worsening economy, one of the highest rates of inflation and unemployment in post-independence India and the increasing commonplace of hate crimes. The writer Arundhati Roy, in episode two of the series, says, “Why do I speak to you on this film? Only so that there’s a record somewhere that all of us didn’t agree with this. But it is not a call for help, because no help will come.” In borrowing her words, I find my reason for daring to write this column as well.

(Deepa Bhasthi Opinion 24 March 2023 Art Review Asia)