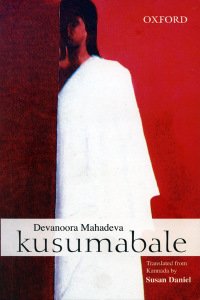

A Modern Kannada Classic Now in English – S R Ramakrishna

[Review about ‘Kusumabale’ english version, by S.R.Ramakrishna. Published in “The New Indian Express” on 05th November 2015] [ಎಸ್.ಆರ್.ರಾಮಕೃಷ್ಣ ಅವರು ‘ಕುಸುಮಬಾಲೆ’ ಇಂಗ್ಲಿಷ್ ಆವೃತ್ತಿಯ ಬಗ್ಗೆ ಬರೆದ ವಿಮರ್ಶೆ. 05ನೇ ನವೆಂಬರ್ 2015 ರಂದು “ದಿ ನ್ಯೂ ಇಂಡಿಯನ್ ಎಕ್ಸ್ಪ್ರೆಸ್”ನಲ್ಲಿ ಪ್ರಕಟಿಸಲಾಗಿದೆ]

Twenty-seven years after Devanoora Mahadeva’s Kusumabale was published in

Kannada, it has made it to English, thanks to Susan Daniel.

Translators familiar with the difficulties of rendering Kannada literary texts into

English will right away salute Susan Daniel’s valiant effort. She brings to an English

readership a book widely regarded as a classic of Dalit writing.

In style, the Kannada original is so distinctive that many readers were confounded.

Since 1988, the book has gone into 15 reprints, so that initial response has made way

for much appreciation. Rangayana has turned it into a spectacular theatre production,

and many in Mysuru can sing the book from memory.Kusumabale is charmingly and

unapologetically sing-song, and draws inspiration from the idiom of the Neelagara story-tellers.

Mahadeva’s narrative also taps into a dialect confined to parts of southern Karnataka.

Yet, Kusumabale is more than a dialect, more than a heroic ballad. Complex characters

from today’s world weave in and out of four story strands. It is a book crafted closely and

lovingly, a delight to anyone who loves the cadences of words.

Kusumabale is the most musical piece of modern prose I have read in Kannada.

Mahadeva takes up the novel, an expansive, leisurely genre, and compresses it for

music, making his expression more poetry than prose, more song than talk.

About 25 years after he had written his original, when I got to meet him,

I asked him about the music of Kusumabale. He said he had listened to Ustad Bismillah

Khan’s shehnai and songs from the film Siri Siri Muvva when he was writing the novel.

Then, again, the music of Kusumabale is way superior to the music of that Telugu hit.

By extracting meaning from sound, Mahadeva becomes a musician first and novelist next.

He cleverly picks words from everyday life and swings them to a folk beat.

These words he plucks, stretches, twangs, caresses, coaxes.

Kusumabale flows like a complex musical composition, stylised in its dramatic

breaks and cadences.

Given that the book’s ‘auditory’ meaning is more difficult to render

than its ‘lexical’ meaning, Susan Daniel adopts some daringly unconventional

methods, retaining Kannada exclamations (ussoh, ay-ay-oh, voh voh),

stringing long sentences, and even employing archaisms.

Masters of modern prose in Kannada are wary of the sing-song, but Mahadeva

proves a contemporary story of love, longing and intrigue can be told in a

language that is simultaneously village and city, ‘folk’ and ‘sophisticated’. Without

doubt, Kusumabale is an unparalleled work of literary-musical art, a classic with no parallel.

Readers of this translation will get a drift of the original, even if some of the

linguistic playfulness is lost.