Devanuru’s book forces us to accept the centrality of casteism in RSS project.

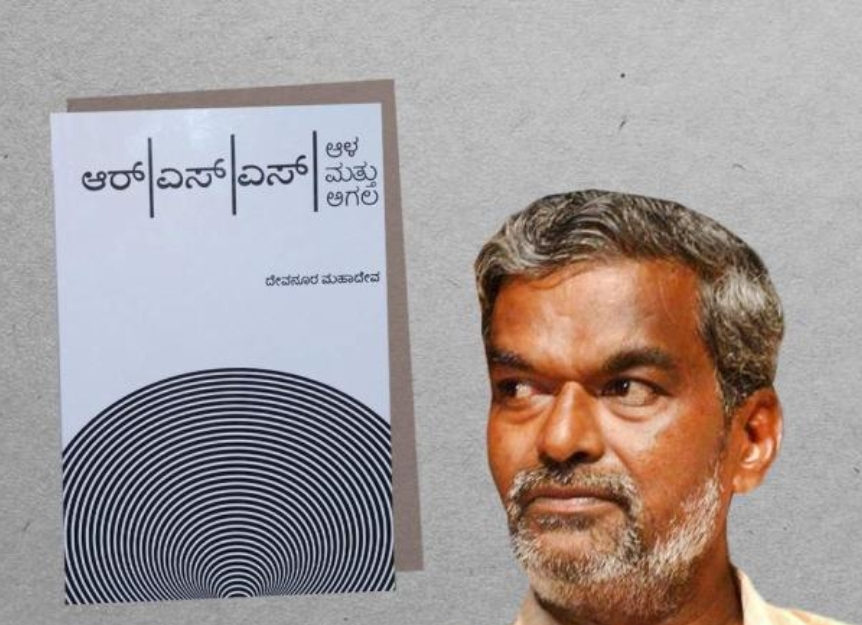

[Devanuru Mahadeva’s book “RSS Ala mattu Agala” Reviewed by Akash Bhattacharya, published in ‘The News Minute’ on January 25, 2023. ‘ದಿ ನ್ಯೂಸ್ ಮಿನಿಟ್’ನಲ್ಲಿ, 2023ರ ಜನವರಿ 25ರಂದು ಆಕಾಶ್ ಭಟ್ಟಾಚಾರ್ಯರಿಂದ ವಿಮರ್ಶಿಸಲಾದ ದೇವನೂರು ಮಹಾದೇವ ಅವರ ಪುಸ್ತಕ “ಆರ್ಎಸ್ಎಸ್ ಆಳ ಮತ್ತು ಅಗಲ” ಕುರಿತ ಬರಹ]

[Devanuru Mahadeva identifies the present moment as a battle between the Indian constitution and the caste system – a key axis of inequality and oppression that the constitution sought to undo.]

Over the last few months, Devanuru Mahadeva’s short and accessible 64-page book giving a comprehensive overview of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has been making waves in Karnataka and beyond. Originally published in Kannada, it sold over 40,000 copies in no time and it was soon translated into multiple Indian languages. The book and its translations have been well received but its message needs even wider circulation.

Divided into three parts, the book provides a thorough critique of the RSS and connects its overall political-ideological programme with the saffron politics of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and a range of ‘autonomous’ outfits such as Sri Ram Sene, Bajrang Dal and others. Laden with quotations from leading RSS ideologues, especially MS Golwalkar, the book is intended for people grappling with the seemingly all-pervasive RSS worldview. That’s you, me, and everyone else living in today’s India.

Mahadeva outlines the core ideological agenda of the RSS right at the outset: to replace the Constitution that promises equality to every citizen, with the Manusmriti that is based on the ‘chaturvarna’ hierarchy. He then talks about the main elements of this agenda: the transformation of our federal structure into a unitary one, disenfranchisement of the minorities and oppressed, imposition of Sanskrit (and Sanskritised Hindi) over people’s languages, and establishing Aryan racial superiority, all heavily inspired by Nazi Germany.

The country has witnessed consolidated resistance against specific policies (discriminatory citizenship laws, farm laws, anti-conversion laws, the National Education Policy, and others) and events (caste atrocities, communal violence, and so on) in recent years. However, these have not congealed into a mass resistance against the RSS and its progenies. To forge powerful solidarities, connecting the dots is essential. Mahadeva does precisely that. It is equally important to acknowledge the centrality of casteism in the RSS project: a point that is yet to be fully recognised in opposition politics. The book pushes us to acknowledge this.

The name of the author lends weight and even greater meaning to this piece of work. We know Devanuru Mahadeva as a Dalit writer and one of the most important figures of the Bandaya literary movement of the 1970s. This movement famously nurtured a generation of Dalit writers and activists, many of whom remain active to this day and embody a much-needed connection between the past and the present. Mahadeva is one of the foremost names on that august list.

RSS: Aala Mattu Agala is firmly grounded in the emerging socio-political currents in Karnataka and beyond. The rise of the RSS is a defining aspect of the current juncture, but so is the renewed unity among Dalit organisations against the former. This unity intersects with unity between Dalit and Left organisations and other democratic forces involved in struggles for plurality and equality.

“Constitution versus caste”

Mahadeva identifies the present moment as that of a battle between the Indian constitution, crafted under the leadership of BR Ambedkar and the caste system – a key axis of inequality and oppression that the constitution sought to undo. He traces the origins of this conflict in the historical milieu of the late colonial period, which produced both the RSS and the democratising currents that created the constitution.

During the decisive decades of the freedom struggle, an influential section of Brahmins organised themselves to guard their self-interest against modern democratic ideas and institutions which facilitated the socio-political assertion of Dalit Bahujans and women. They found a useful role model in European fascism and soon developed a Hindu supremacist ideological framework to preserve the caste order. As the RSS entered politics in the 1950s through the Bharatiya Jan Sangh (BJS), and later through the BJP since 1980, the political implications of their ideology have come to the fore. Its desire to ensure the continued supremacy of the caste system has led them to try to wipe out other religions that originated in India such as Jainism, Buddhism and Lingayat, whose very origins were out of contempt for the caste system, writes Mahadeva.

As a natural corollary, “pluralism is rupture, separationist, a poisonous seed” for the RSS. So is the Indian constitution which sought to replace caste-based laws and ethics with a notion of democratic citizenship. So powerful is the Constitution that the RSS has needed a radically alternative political framework to house its agenda. The fascist “one flag, one nation ideology, and Hitler’s one race, one leader all-powerful authoritarian governance,” supplied them with a useful point of reference. The notion of Aryan supremacy and racial purity is an essential ingredient of their belief system. Mahadeva points out that here too, Hitler’s Aryan supremacist racist thought has been an inspiration for the RSS. He suggests that the politics of erasure of identities and attacks on indigenous peoples’ rights that we are witnessing today is a direct consequence of Aryan supremacist beliefs.

Manipulation of history is a key discursive strategy of the RSS. Mahadeva uses the debate on the Indus valley civilisation as an example to illustrate this point. Recent DNA studies at Rakhigarhi on the ancient fossil DNA have revealed the absence of any Aryan or Vedic lineage within the genealogy of the people of the Indus valley civilisation. Shocked by this, the RSS has begun demanding the ‘Indus valley civilisation’ be renamed as ‘Saraswati civilisation’. As far as policies go, the book refers to a range of contemporary developments – from GST (goods and services tax) to privatisation, from the ban on hijab to passing of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and anti-conversion laws – as the direct outcome of the RSS belief system. Religious polarisation, systematic discrimination against Muslims and Christians, subversion of the federal structure and deliberate damage to public systems such as education that facilitate social equality and upward mobility of Dalit Bahujans and women – each of these takes the RSS closer to realising its agendas.

“An anti-fascist manifesto”

Mahadeva refrains from using the term ‘fascist’ to refer to the RSS, even though he eagerly draws out its fascist antecedents. Perhaps he is being mindful of the different historical contexts in which European fascism and the Indian saffron brigade have thrived. Perhaps it is also due to the unique mode of operation of the Sangh which he correctly defines as “non-constitutional association/organisation-controlled party politics.” The semantic difference notwithstanding, Mahadeva’s correct identification of the nature and objectives of the RSS, and his passionate call for resistance make his book a powerful anti-fascist manifesto.

Mahadeva’s appeal to the Hindu community is quite remarkable. Mahadeva avoids using the word ‘Hindutva’, presumably due to its positive connotation among large sections of Hindus. At the same time, he implores Hindus to see through the saffron project and to reject the RSS’s claim of representing all Hindus. He quotes Swami Vivekananda, whom the Sangh has eagerly appropriated, to demonstrate that the Bhagavad Gita – a key text in saffron pedagogy – is a later interpolation into the Mahabharata. Mahadeva departs from the two dominant tendencies in the ‘Hindus against Hindu supremacism’ frame of thought. He neither calls for a rescue of Hinduism nor does he ask the average Hindus to downplay their religious subjectivity and reject saffron politics purely due to the economic damage it is causing. This creates the possibility of a radical resolution of Hinduism versus Hindutva conundrum.

Instead of ‘rescuing Hinduism’, we could work towards building a new democratic culture – a ‘prabuddha’ consciousness – based on pre-modern dissenting traditions (Dalit Bahujan, feminist, and others) and modern democratic and humanist ideals. Mahadeva does not say this explicitly but his refusal to fall back on the ‘rescue Hinduism’ framework makes this a potentiality. Mahadeva’s presentation also raises troubling questions to which, one wishes, the book provided some answers. How did an organisation with clear fascist objectives manage to successfully work its way over time into India’s constitutional system? How did a country that voted out a BJP government (led by AB Vajpayee) in the aftermath of the Modi-led Gujarat pogrom come to accept the latter as a national leader within a decade?

While pointing out the specificity of the RSS and the potent threat that it carries, Mahadeva sometimes appears a bit soft on previous unjust regimes, somewhat downplaying the horrors of the Emergency. One also wishes that the author included a sharper analysis of capital in the book. The rise of the BJP under Modi cannot be explained fully without considering big corporate support for the regime. Notwithstanding these concerns, the book is a must-read for all citizens who believe in plurality and equality. The book reminds us that the RSS project is, above all, an ideological project. This implies that the task of pushing back the saffron project must be accompanied by a creative counter-hegemonic strategy.

Indigenous traditions of social critique, viz. Dalit Bahujan and Adivasi traditions, feminist, Marxist, and multiple regional peoples’ democratic traditions, are important resources that we must draw upon in building a counter-hegemony. Perhaps mobilising these traditions to build a new democratic society is the only way in which we can save these from being muted or crushed by the RSS juggernaut.

(Akash Bhattacharya is an independent academic and political activist affiliated to CPI-ML (Liberation). He taught history and education at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru, from 2019 to 2022. Views expressed here are the author’s own.)