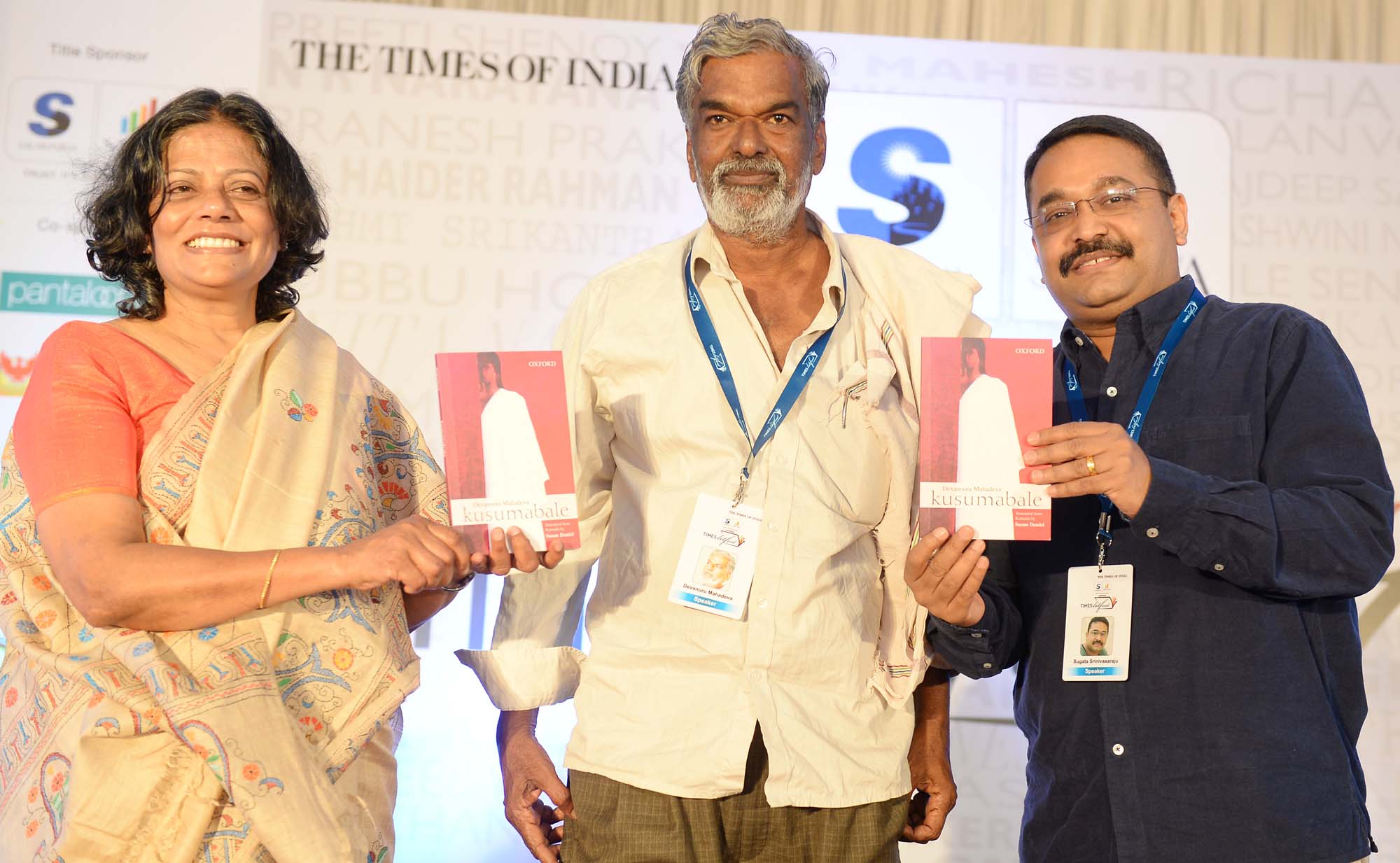

Susan Daniel’s, Interview by Times of India,

English professor Susan Daniel has translated Devanur Mahadeva’s popular Kannada novel, Kusumabale, into English. Published by the Oxford University Press, the book was released recently at the Times Litfest. Daniel shares her experience of translating one of Devanur’s most powerful novels. Excerpts from the interview:

What made you select this book for translation?

The desire to translate Kusumabale was a whim to begin with. I read the novel soon after it was published. I can’t claim to have understood it completely at that time. All the same, it left a lasting impression on me, and I remember coming away with the feeling that it had more to offer. Years later, when the wish to translate it seized me, I was only reconfirming that first impression. Although Kusumabale has only about 120 pages, written in both prose and poetry, it is an intrinsically complicated and difficult text to render. Rendered into English, there is always the fear that not just the nuances, but also those “truths” of Dalit life – accessible only through the understanding of the very creative use of the Dalit dialect – are in danger of being lost.

How did you plan the translation?

I had no track record as an established translator when I asked the author, Devanur Mahadeva, for permission to translate this novel. My early schooling was in Bengaluru – at an “European school” that had very few Indian teachers. When we moved from the heart of the city to live on the outskirts, apart from the agricultural land around the house, there was also a tannery that had shut down. The people who worked there were rendered jobless, but continued to live in a settlement close by. Sometime after, my father started a school on the premises for the Dalit children of the area and called it Navjeevan, Gandhiji’s word for social upliftment. Yaada and Amasa in Kusumabale became those children of my childhood, who wouldn’t go away from my memory. When we moved to Sagar from Bengaluru, I was to meet and interact with the Nayaks of the area. Kamalakka and Beerajja’s speech in turn were to resonate in the voices of Turamma, Kempi, Garesidda and others. It was in Sagar that I woke to the horrors of casteism. From there to Mysore as a student of literature, my education was rounded off with the discourses started by the Women’s movement and the Dalit and Farmers’ movements. I have no doubt that these influences came back to help me assist me with my ‘wish’ to translate this novel. And what better work than Kusumabale to get a view of the Dalit world?

How long did it take you to complete the translation?

A good translation, like good pickle or wine, has to age. Every translation has to first see its translator go through a process of interiorisation, before it can make out something for the reader. This translation stretched itself over three years from permission to publication, with space to accommodate all my first readers. Just as one would use Joyce’s Ulysses as an aid to translate Homer, so did I use L Basavaraju’s Kusumabale in verse format, to assist me. Although L Basavaraju’s changed format makes for an added element of drama, it helped greatly to keep a tab on my own drafts. And that is why I would like to see L Basavaraju’s verse format of Kusumabale as the first translation – albeit into the same language!